The building at 1330 Glenarm Place in Denver feels out of place against our thoroughly modern skyline. Maybe it’s the slightly weathered red brick façade, or the green and gold fabric awning which stands sentry over a heavy wooden door.

The home of the Denver Press Club harkens to an older Denver, before the silicon rush of the 1990s and its high-tech settlers. It predates the pot-rush of the 2010s, with older, more prehistoric vices.

Stepping inside is stepping back in time. A too-narrow staircase to the basement crouches to the left and a wide passage to the right beckons visitors toward the bar through the open living room. The space is well-lit, with a large window facing the street. Wooden floorboards creak slightly and point at the mantle. A cozy fire burns in the fireplace and a tinkle of glassware can be heard above the din. The atmosphere smells of old churches and citrus groves. Musky panels adorn the walls, and comfortable chairs pen a coffee table below a television that is almost never on.

On a busy night, regular members mix with guests and curious bystanders. The mood is occasionally raucous but rarely rowdy. Local journalists hold court at the bar as curious students wander through, examining the faces in the frames.

Here is former President Woodrow Wilson, who visited the club during his tenure, presumably before his stroke. There is Gene Amole, Carl Akers and Stormy Rottman–frozen in caricature and memory–proudly displayed throughout the dining room.

There is a waft of nostalgia here and a hint of pure mythology. It isn’t widely known to the lay, but journalists love mythology. Member [editor’s note: ME] Jonathan Rose describes the Press Club’s general milieu as “musty, with the scent of the intrepid, and a hint of the liquor in which they’ve wallowed.”

A working description to be sure, but only a first draft. Everything here is in-between the draft and the denouncement.

Beneath the veneer of retro-chic is a growing current of the new blood. In its heyday, the Denver Press Club was home to thousands of working scribes. Hacks and cubs from two local dailies frequented the spot to melt away the strain of the day. Stringers and columnists jockeyed for space at the bar as broadcasters, commentators and contributors hovered around a poker table, downstairs, near three phone booths and a billiard table covered in traditional red felt.

The membership roster is leaner now, but rarely mean. One of Denver’s dailies is history and the other is moving out of its storied downtown location. Bloggers and PR hacks have joined their counterparts in the old press and the club hosts seminars on artificial intelligence, taxes for freelancers and #metoo.

The Damon Runyon award presentation is still one of the largest – and most prestigious – of calendar events.

Poker games are still offered and joined on Wednesdays and Thursdays, even as the Society of Professional Journalists meet and mix in the living room on the first floor. The bathrooms are clean, and the drinks are cheap and dirty. Handshakes are offered freely, and new members are welcomed with friendly smiles and shaggy dog stories.

If you believe them, a ghost of rage still howls next to the safe behind a locked office door. The battlefield has changed, but the siren song remains.

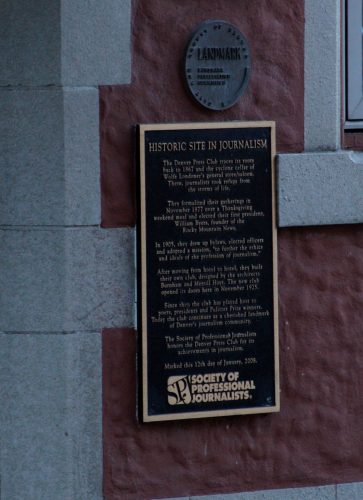

This is the nation’s oldest, free-standing press club. An historic artifact–past, present and future–stirred in a cocktail of symbols, words and legends. Its members are the working initiated, the self-declared elect of the world’s second oldest profession. Ink gods willing — they’ll always have something to say about the first.