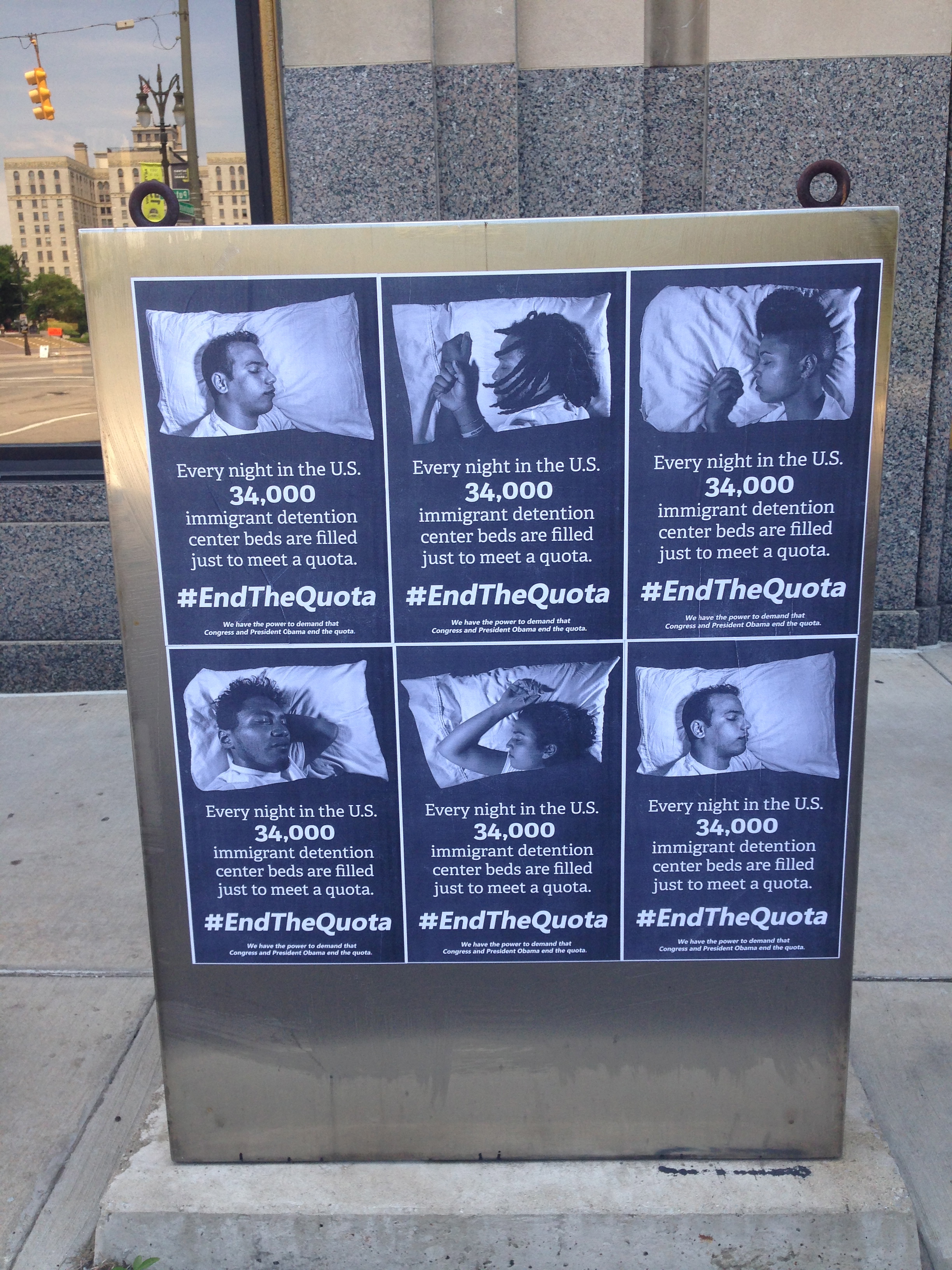

While America’s problems with excessive incarceration have received increased attention, until recently, immigration detention has been conspicuously absent from this discussion. In the wake of each year, about 400,000 people are placed in immigration detention. On any given day, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) keeps at least 34,000 immigrants incarcerated while they await a hearing with an immigration judge. This arbitrary (and incredibly high) number is mainly attributable to the so-called “detention-bed mandate,” an arbitrary quota set by Congress that ICE needs to meet. The quota is written into the federal law that appropriates funding for ICE. Congress requires the agency to “maintain a level of not less than 34,000 detention beds” at any given time. The quota, first enacted in 2007, is an oppressive aberration—no other federal agency is required to detain a certain number of people.

This is the third of a three part series examining immigration detention in these United States, featuring policy recommendations by Antoaneta Tileva. You can read the first part here.

Policy Recommendations

- End the Quota.

The detention bed quota is an absurd mandate with a tremendous human and financial cost. No federal or local enforcement agency detains based on a quota—the cruel perversity behind such action is apparent. The very idea that people are detained not because of any crime they have committed or because they pose a risk to their community but to meet an arbitrary number that benefits private interest is morally reprehensible.

Over half of immigrant detainees between 2009 and 2011 had no criminal history. If certain individuals need to be detained based on measurable criteria such a prior criminal record of grave, felony-level offenses, then immigration detention should be reserved for those individuals only; it should never be based on an arbitrary, yet mandatory quota.

- Create Non-Penal, Community-Based Alternatives to Detention.

If the goal of immigrant detention is to ensure compliance with court hearings and final orders of removal, detention is not needed to meet those goals. ICE has a spectrum of supervision options, including community-based alternatives, bond, and GPS-enabled ankle monitors, which cost between 70 cents and $22 a day—a fraction of the cost of detention. The average immigration detention bed cost $158 per night in FY 2013, compared to $10.55 for the average daily cost of alternatives to detention programs.

People in alternatives to detention programs appear in court 99% of the time and comply with removal 84% of the time. In 1999 and 2000, Catholic Charities of New Orleans administered an effective, self-funded ATD program for indefinite detainees with criminal records and asylum-seekers. Both of these programs achieved high rates of compliance. Similarly, the Vera Institute for Justice’s pilot “Appearance Assistance Program” from February 1997 to March 2000 achieved an overall court appearance rate of 90 percent.

There are two types of alternative to detention (ATD) programs. The first type relies heavily on technology, extensive reporting, monitoring, and visitation. The second relies on community-based support and case management services. At present, ICE funds two large ATD programs of this kind, “full service” and “technology assisted” ATDs. In the full service program, contractors use a combination of case management and monitoring, including the use of tracking devices and home and office visits. Technology-assisted programs use only monitoring technology and do not include case management services. Between FY 2011 and 2013, the full service ATD program yielded an appearance rate of 99 percent at court hearings and 95 percent at scheduled final removal hearings. ICE does not collect or report on similar performance results for the technology-only program.

It is incredibly important that these programs be “alternatives to detention,” and not “alternatives to release.” Programs that are overly restrictive and stigmatizing such as electronic monitoring and home confinement should not be used when an individual could be released on bond or to a case manager, for example. Case managers educate and assist participants to comply with ICE and Immigration Court reporting requirements, and help them to secure legal assistance. These programs also work to integrate persons who may be eligible to remain in the United States via job readiness and placement services. They assist persons who are ordered removed to establish contact with family and other support systems in their countries of origin.

The quasi-punitive nature of the current system must be eliminated.

- End Reliance on Prison-for-Profit Modes of Detention.

It is clear that any system that relies on the very companies that stand to profit from the detention of people is flawed. Public detention paradigms have greater transparency, accountability, and oversight by watchdog and civil liberties groups; for-profit prisons provide a perverse economic incentive to skimp on human necessities. The lobbying efforts of private prisons ensure their stronghold on policy makers.

- Increase Funding Available to the Immigration Court System. Provide Legal Counsel and Case Managers to Poor Detainees with the Extra Funding.

Congress should also appropriate far greater amounts to the Immigration Court system in order to expedite hearings, to reduce court backlogs and, by extension, to reduce detention and alternative to detention costs.

The detention system has become an enormous funnel for the crushingly overburdened, underfunded immigration courts, which receive a meager $300 million from Congress each year, one-sixtieth of what ICE and Customs and Border Protection get. By the end of March 2015, nearly 442,000 cases were pending before immigration judges, with an average case waiting 599 days to be heard, and delays in some courts of more than two years. This is a far cry from due process.

While noncitizens in removal proceedings have the right to be represented by counsel at their own expense, many detention facilities are located in remote areas making it difficult for detainees to seek an attorney. On average, 84% of detained immigrants go through proceedings without legal representation.

Funding for the U.S. immigration court system should increase by an order of magnitude. This would diminish case backlogs which now average more than 18 months, allow for the timely adjudication of cases, and obviate the need for costly and prolonged detention. Prolonged detention should be statutorily prohibited, whether for persons whose removal proceeding are pending or for those who have received an order of removal.

Immigration judges or judicial officers should be vested with the authority to make custody decisions soon after detention for every person facing removal, including those subject to expedited, summary, administrative, and non-court removals. In addition, all persons facing removal should be afforded a hearing before an immigration judge. Finally, detention makes it far more difficult for indigent and low-income immigrants to secure counsel and, as a result, to present their legal claims for relief and protection, including asylum. Given its responsibility to afford due process, the U.S. government must fund legal counsel for indigent persons in removal proceedings, particularly detainees.

Leave a Reply