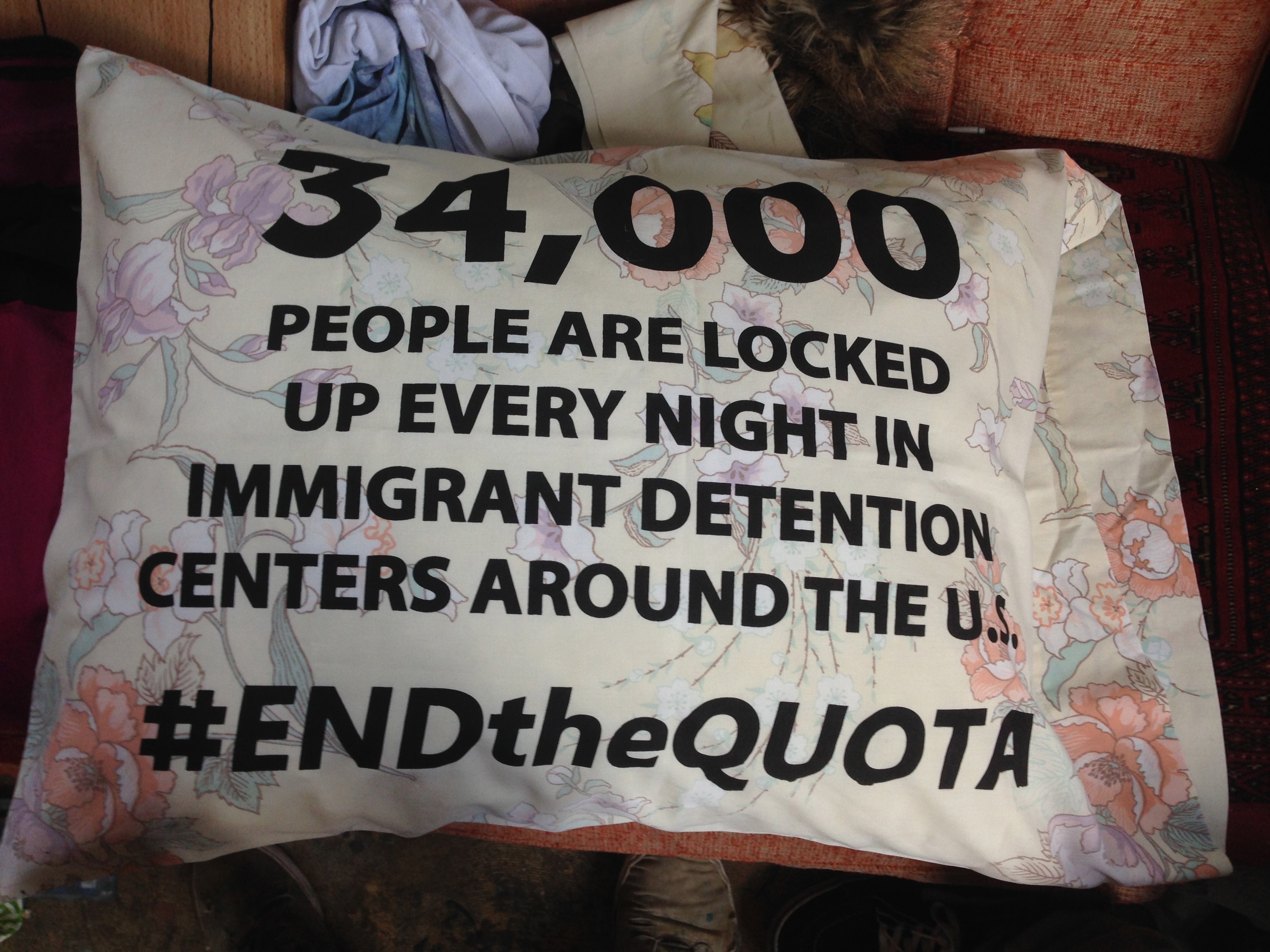

While America’s problems with excessive incarceration have received increased attention, until recently, immigration detention has been conspicuously absent from this discussion. In the wake of each year, about 400,000 people are placed in immigration detention. On any given day, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) keeps at least 34,000 immigrants incarcerated while they await a hearing with an immigration judge. This arbitrary (and incredibly high) number is mainly attributable to the so-called “detention-bed mandate,” an arbitrary quota set by Congress that ICE needs to meet. The quota is written into the federal law that appropriates funding for ICE. Congress requires the agency to “maintain a level of not less than 34,000 detention beds” at any given time. The quota, first enacted in 2007, is an oppressive aberration—no other federal agency is required to detain a certain number of people.

This is the second of a three part series by Antoaneta Tileva examining immigration detention in these United States. You can read the first part here.

Human Cost

Detention often results in family separation, especially for individuals detained in remote facilities far from their home, a problem that can be exacerbated by the need to fill detention beds in facilities across the country. Family separation and the resultant care and economic insecurity deeply scars individuals and communities; detainee abuse such as denial of water, medical treatment, adequate nutrition, or physical safety is far too rampant and, even worse, ignored. Because for-profit prison corporations are private, they’re not required to comply with the Freedom of Information Act. That means they can refuse to disclose their policies and earnings, which would not be permissible for a government-run prison. Despite its characterization as civil confinement, a closer look at immigration detention reveals that is often harsher than criminal detention. Immigration detainees are often held in similar units to criminal detainees, with conditions that include shackling, solitary confinement, and lack access to proper nutrition, exercise, and basic healthcare. In fact, there have been 111 reported deaths in immigrant detention facilities largely due to improper medical attention and suicide.

Financial Cost

Immigration detention is costly. The United States spends about $159 per day to detain one individual and about $2 billion annually on immigration detention.

Put Out/In the Cold…(A Day in Life Of)

The GEO Group runs the Karnes family jail in Texas. The company holds immigrants at 15 ICE detention centers in six states; the facility in Karnes County, Texas, was opened especially for Central American moms and their kids. The annual contract is worth $26 million.

“One of the bleakest moments during my week as a volunteer attorney was when I had to explain to one of the women that the logo on all of the staff polo shirts belonged to a company and not to the federal government. When I told her that this company receives a certain amount of money per day for every bed they fill, including that of her 3 year-old daughter, she shook her head in disgust and cried,” reports attorney Mich Gonzales.

“All of the women told me about the time they spent in the so-called hieleras (ice boxes) after being apprehended by the Department of Homeland Security. Each one recounted in detail how gruff border patrol agents initially detained them in a steel-like room with no beds and no windows. They all spent two days and one night in the first hielera that was so cold that no one could sleep, and the children cried day and night. They were all given a small sandwich they each described as barely edible for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Each recounted how their children refused to eat. Then they were all moved from the first hielera to a second hielera where they spent three days and two nights. This one, they explained, at least had mattresses strewn on the floor, but was still freezing cold and the food remained unchanged.”

“All of the children I met that week were sick with a visible sinus cold or flu. None had eaten well in the last two weeks since being in the US government custody. None had been given medicine, despite requests. Some of the toddlers were still nursing and others were so exhausted that they slept in their mother’s arms throughout my one to two hour interview. All of the women complained that the rooms were too cold at night. They sleep four bunk beds (eight beds) to a single room. They are issued only one sheet per bed. Instead of having their children sleep in a separate bed, they sleep together in the bottom bunk. They explained how they use the sheet from the top bunk to create a shield around the bottom bunk from the cold air blowing through the vents. They all asked guards and officers repeatedly to please adjust the air and were refused.”

Legal Context

Immigration detention in the United States is “civil” detention. From a legal standpoint, this means that an individual placed in immigration detention is not entitled to the same protections that would apply if he or she were being incarcerated for a crime (habeas corpus doctrine). Individuals charged with crimes, whether citizens or not, have constitutional protections against lengthy pre-trial detentions. They also have a right to counsel at the government’s expense to assist in their defense. In contrast, immigration detention is not subject to the same set of procedural protections. The Supreme Court articulated this distinction in the 1896 case of Wong Wing v. United States, in which the Court concluded that “detention or temporary confinement, as part of the means necessary to give effect to the provisions for the exclusion or expulsion of aliens,” was “not imprisonment in a legal sense” (Wong Wing v. United States, 163 U.S. 228).

In this legal construction, immigration detention is simply a holding mechanism; it is not (supposed to be) punitive. Because immigration detention is not treated under the law as a criminal punishment, immigrants are frequently detained pending removal proceedings in the absence of any individualized showing that the immigrant poses a danger to the community or is a flight risk. Some of the traditional constitutional protections inapplicable in the immigration context include the privilege against self-incrimination, the right to trial by jury, the prohibition on ex post facto laws, the right to appointed counsel, and the ban on cruel and unusual punishment. The Fifth Amendment requires immigration proceedings to be “fundamentally fair.” But statutes and regulations not the Constitution-provide specific due process protections because Congress creates federal immigration policy.

On October 29, 2015, two rulings by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in California, respectively, established that detainees have the right to a bond hearing while they are fighting their deportation cases. The outcome of those rulings is that thousands of immigrants, legal or not, who were held for indefinite periods now have the right to a release hearing where it will be up to an immigration judge to decide whether they are dangerous or present a flight risk. The courts’ rulings apply in the states covered by those circuits.

The Ninth Circuit, in Rodriguez v. Robbins, ruled that the government has to justify “by clear and convincing evidence that an alien is a flight risk or a danger to the community to justify denial of bond.” It also ruled the government has to consider alternatives to detention such as electronic monitoring devices. Finally, it said detainees should get a bond hearing every six months.

In a more limited ruling, the Second Circuit in New York, in the case of Lora v. Shanahan adopted what it called “a bright-line rule” that detainees must get a hearing within six months of his or her detention. On August 22, 2014, the American Civil Liberties Union, the American Immigration Council, and the National Lawyers Guild filed a federal lawsuit claiming that the government committed egregious due process violations against women and children held for deportation at a detention center in New Mexico. The lawsuit claims that the administration has rigged the system so that vulnerable women and children who plead for asylum can’t get it. It says the immigrant detention center in Artesia is a middle-of-nowhere prison in the desert, 200 miles from the nearest big city, that short-circuits legal access and due process for the sake of swift and sure deportations.

The lawsuit details how detainees in Artesia are cut off from the outside world, and subjected to a “highly truncated process” that denies them crucial information and assistance. Asylum officers and judges rush detainees into answering questions on things about which they may be confused or uninformed. Detainees lack access to phones; lawyers lack access to detainees. They are locked out of hearings and denied interviews. Mothers are required to explain the reasons they fear persecution — that is, describe abuses like death threats and sexual assaults — in front of their young children. Children are not screened individually to see if they may have their own claims to asylum.

In the Artesia center, officials set up a courtroom where immigration judges hear asylum cases by video-teleconference and asylum officers interview migrants to make initial assessments of their claims. But according to the lawsuit, the center does not provide conditions for legal advocates to represent the migrants or inform them of their rights. Telephone communications are severely limited, and lawyers routinely had trouble meeting with migrants and were denied access to hearings and interviews.

Mothers were required to be interviewed with their children, and they reported being reluctant to discuss threats, sexual abuse, and violence they faced.

On August 21, 2015, in a critical legal development, federal District Court Judge Dolly Gee of Central California ordered the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in Flores v. Lynch to begin releasing from immigration custody children and their accompanying parents. This followed the court’s July 24 ruling that a 1997 settlement Flores v. Reno—which initially set standards for the release, detention, and treatment of unaccompanied children in federal immigration custody—also applies to accompanied minors, or those apprehended with a guardian. Under the settlement’s terms, children must be released from detention “without unnecessary delay” to a parent, relative, or other guardian in the United States, and when in detention, held in the least restrictive setting in non-secure facilities specially licensed to care for children. Judge Gee found that DHS’s practice of holding families in detention for long periods violates that settlement. She also ordered DHS to improve the “deplorable” conditions in Border Patrol stations, where children and families are often initially held for several days. Judge Gee gave DHS until October 23 to comply with her August order, and denied the government’s request to reconsider her July ruling. The Justice Department is considering whether to appeal the release order. Meanwhile, DHS has said it will continue to detain families apprehended at the border, as the order provides for an exception during periods of heightened child migration.

Leave a Reply