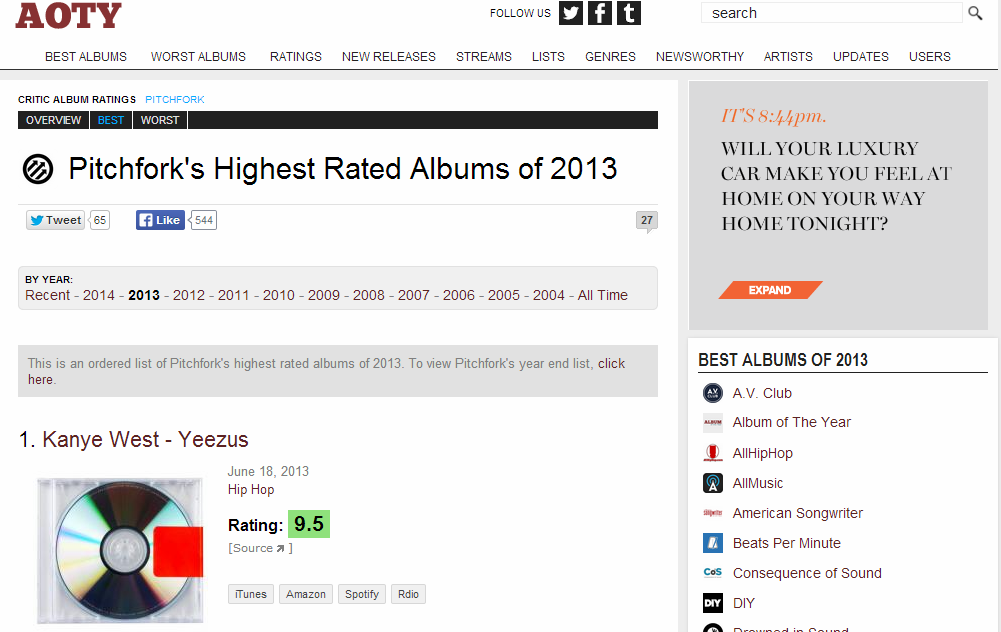

Best Albums of 2013. Best Books You Never Read in 2013. Best movies, best video games, best sasquatch erotica. Surely the annual “best” lists that websites, magazines and newspapers publish New Year’s Day intend to inform us–not to mock aging hipsters for all the pop culture they missed in the previous year. The lists spotlight the best in media and art in a short, succinct way, easy to digest on our iPhones and Androids. But each new year, the breathless rush to catch up with every unheard band and every unread book that NPR nods to or Pitchfork pitches inevitably engenders a sense of impotence. I might remember a band name, but not what their music sounds like. I’ll know that Vampires in the Lemon Grove made several lists of best books, but I won’t remember whether it’s a collection of short stories or the latest Twilight knock-off. Because there’s just too much information.

To be sure, information is never a bad thing. “Information can be wrong but never bad” is my mantra for friends fretting about whether to tell their kids the clinical names for genitals or to call them “wee-wees,” whether to tell them where babies come from or to summon the stork. The fact that anyone with an Internet connection can access all this information and art leads to both excitement and frustration. Oppressed people organize coups on Facebook, and shaky phone videos lead investigators to terrorists. Of course knowledge is power. Of course. But each January, these “best of” lists remind me that I will never have the capacity to absorb the nearly infinite smorgasbord of news, opinions, photographs, videos, status updates and talking cats that the Internet has spread before me. The big threat of this onslaught of information isn’t that I’ll miss out on a talking point for a party, but that my brain has changed in a frightening way.

The Internet makes skimmers of bookworms, Googlers of philosophers and summarizers of writers. The modern attention span is a pathetic little wisp, and we’re expected to keep packing in more or risk losing our jobs and social lives.

The Internet makes skimmers of bookworms, Googlers of philosophers and summarizers of writers. The modern attention span is a pathetic little wisp, and we’re expected to keep packing in more or risk losing our jobs and social lives. It’s easy to see why author Nicholas Carr argues in The Shallows — a Pulitzer-nominated book I made it halfway through — that the Internet is not just changing the way we receive information, it’s actually changing the neural connections in our brains. Carr laments the loss of deep thought required to simply read a book. “I used to find it easy to immerse myself in a book or a lengthy article,” Carr writes. “My mind would get caught up in the twists of the narrative or the turns of the argument, and I’d spend hours strolling through long stretches of prose. That’s rarely the case anymore. Now my concentration starts to drift after a page or two.” The fear of losing the ability to get lost in a book haunts me.

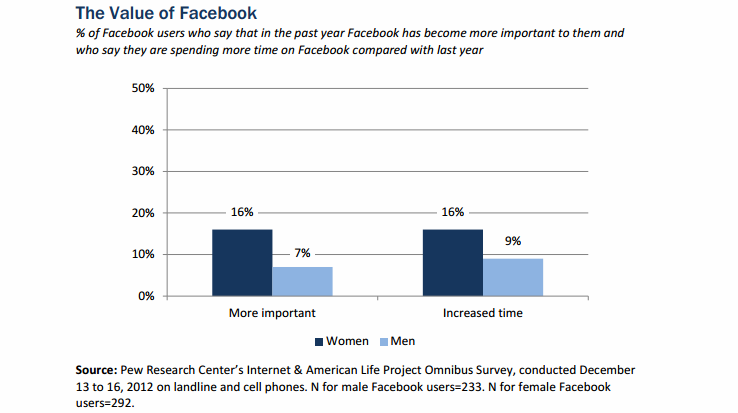

My teenage self would roll over in her vinyl pants. I used to really listen to music — I didn’t just Spotify a band’s most popular song and judge it within 30 seconds. I played In Utero on repeat while lying on my bedroom floor and squinting at the CD booklet under the glow of a blue light bulb. I highlighted passages in Catcher in the Rye and folded down page corners in Life After God so I could return to my favorite words again and again. It was during those teenage years that a science teacher taught me about carrying capacity: the maximum population size of a biological species that an environment can sustain indefinitely. My brain is the environment. My memories, attention span and relationships are the species struggling to survive in that limited space. “What the Net seems to be doing is chipping away my capacity for concentration or contemplation,” Carr writes in The Shallows. “Whether I’m online or not, my mind now expects to take in information the way the Net distributes it: in a swiftly moving stream of particles. Once I was a scuba diver in the sea of words. Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.” I think most tech-savvy adults admit to feeling this way sometimes, but there’s little we can do about it when our friends limit party invitations to Facebook events and our bosses expect us to reply to emails sent at 10 p.m.

A Pew survey in early 2013 found that 67 percent of online American adults use Facebook, and 61 percent of those users reported voluntarily taking a break from the social network for a period of several weeks or more. The Number one reason? “Too busy.” But it’s not only friends who expect us to be connected all the time — it’s our employers. As the BlackBerry takes its last gasp, I say good riddance to the smartphone that put instantaneous communication in our tendonitis-inflamed palms. With that ability to connect 24 hours a day came the expectation to connect 24 hours a day. We leave work at 5 and feel guilty at 9 when a ping on our phone tells us our co-worker is rushing to finish a project while we down a glass of Two-Buck Chuck. If this glut of information and connectedness made us better at our jobs, maybe it would justify the downsides. But it’s only made our jobs more convenient, not higher quality. People often misuse the figure of speech “jack of all trades” to describe someone who’s talented in many areas, but they leave off the second part of the actual phrase — “master of none.”

In The Orchid Thief: A True Story of Beauty and Obsession, Susan Orlean writes about her investigation into the poaching of rare orchids. She delves into the subculture of people obsessed with plants. “The world is so huge that people are always getting lost in it,” Orlean writes. “There are too many ideas and things and people, too many directions to go. I was starting to believe that the reason it matters to care passionately about something is that it whittles the world down to a more manageable size.” But I didn’t copy that passage from the book; I found it on a website because I haven’t read the book. My bipolar artist friend quoted it during a conversation about her obsessions. I told her I would read The Orchid Thief, then indexed it in my mental list of books I need to read this year. The list is written in ink that fades with each new entry. But the book was made into a movie that’s on Netflix, so maybe I’ll absorb some of its beauty after all, in a faster and more convenient way.

Leave a Reply